Answering the call of those who are unheard

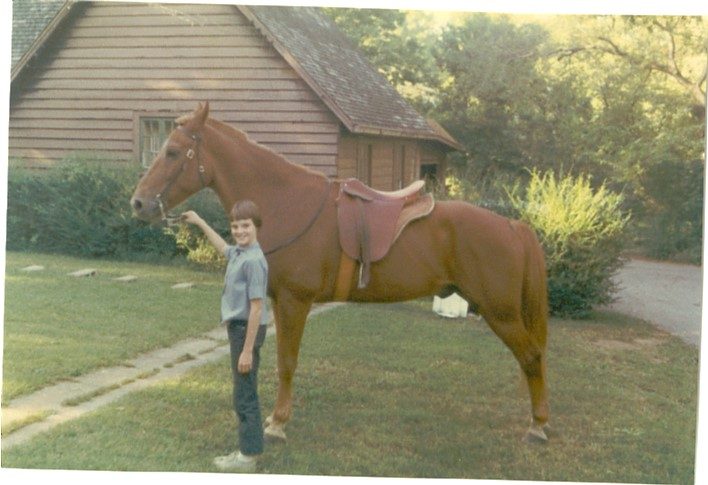

Growing up with horses is among my best childhood experiences. Our home at the time was in the city but in an area that had two-acre lots, and ours had stables with large, fenced enclosures across the back of the property. At various times we had a goat, a pair of Easter ducks that lived for over a decade, a pet rabbit, and even a bull calf briefly in residence. The very best animals, though, were horses. The first a neighbor brought from his farm for his son and me to enjoy when I was only six years old. A second was bought by different neighbors for their daughter, my best childhood friend, and stabled on our property. In between those two wonderful beauties, a pony surprisingly appeared on my tenth birthday in one of those magical, Disney-esque moments. (Thank you, Jones family!)

Growing up with horses is among my best childhood experiences. Our home at the time was in the city but in an area that had two-acre lots, and ours had stables with large, fenced enclosures across the back of the property. At various times we had a goat, a pair of Easter ducks that lived for over a decade, a pet rabbit, and even a bull calf briefly in residence. The very best animals, though, were horses. The first a neighbor brought from his farm for his son and me to enjoy when I was only six years old. A second was bought by different neighbors for their daughter, my best childhood friend, and stabled on our property. In between those two wonderful beauties, a pony surprisingly appeared on my tenth birthday in one of those magical, Disney-esque moments. (Thank you, Jones family!)

My best friend and I rode the horse and pony (bareback, mostly) all over the neighborhood. A favorite route took us across big lawns to the meadow hidden at the end of some undeveloped woods. With minimal supervision, we cared for those equines in what I now take to be a remarkable hand-off of responsibility to two young, city girls. I often joke that my horses were a large factor in my escape from being certifiably bonkers owing to other much-less pleasant childhood experiences (although I’m aware that positive perception is sometimes debatable).

I had limited contact with horses after those times, and I always missed them. Occasionally, I visited the mounted-patrol police horses, whose barn had public visiting hours. After they knew me, I sometimes got to help groom, but my spirit always wanted more time with horses. In retirement, I’ve had the leisure for mindless Internet scrolling, and I’ve found great enjoyment in watching horses. I especially love the work of horse-rescue organizations, and I follow several non-profits with that mission. Their inspiring efforts also offer a wealth of information about these magnificent creatures – highly social herd animals who form deep bonds with one another and with kind humans. Many horse people believe that a solitary horse is usually lonely and instinctually misses a herd, even if it never experienced being part of one. From my clinical knowledge of equine therapy, I knew that horses also are highly sensitive. I had no idea, though, how that plays out in their equine relationships when they have the freedom to choose.

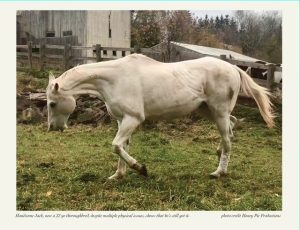

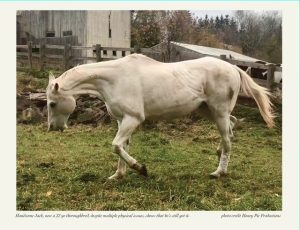

The following story about a horse named Jack was recently shared by Rosemary Farm Sanctuary, a large rescue organization located in upstate New York. https://www.rosemaryfarm.org/ [Photo credit to Honey Pie Productions.] The unnamed writer shared that Jack “lost his herd” when they were turned out for the night. Jack got distracted, and the other horses were out of sight in the huge, hilly sanctuary before he realized that he was alone. Jack’s history before his rescue is lost, but at some earlier point he had throat surgery that cost him his ability to neigh. Horses whinny or neigh as part of their communication, and it’s a critical tool for locating other horses in a herd. Without his neigh, Jack had no way to find his friends.

The following story about a horse named Jack was recently shared by Rosemary Farm Sanctuary, a large rescue organization located in upstate New York. https://www.rosemaryfarm.org/ [Photo credit to Honey Pie Productions.] The unnamed writer shared that Jack “lost his herd” when they were turned out for the night. Jack got distracted, and the other horses were out of sight in the huge, hilly sanctuary before he realized that he was alone. Jack’s history before his rescue is lost, but at some earlier point he had throat surgery that cost him his ability to neigh. Horses whinny or neigh as part of their communication, and it’s a critical tool for locating other horses in a herd. Without his neigh, Jack had no way to find his friends.

The writer beautifully portrays Jack’s increasing distress as he searched, even returning to the medical barn to see if they were there, and then his frantic agitation when they were not. With wonderful detail, the author describes ultimately persuading Jack to follow as they began to look in more distant pastures, and how this huge thoroughbred danced behind her as she called the names of various horses in his herd. Eventually, one answered with a neigh, and Jack immediately started to calm. After several more minutes of human-to-horse communication, they came upon the herd, and Jack happily thundered past the writer to meet his companions. The moving post ends with a simple commentary on how much all of us want to be at home, to be with our chosen ones. The sweet story resonated with thousands of readers, including deeply with me.

I was also immediately struck by another takeaway beyond the pull and comfort of finding your people and feeling at home. That compassionate, dedicated, helpful human “heard” Jack’s voice, even when the horse couldn’t speak for himself. She recognized his distress, understood the importance of his being with the herd, and went out of her way to reconnect him. She bridged the silence between his deep need and his wounding that removed his voice. She spoke for him, kept calling on his behalf, until others heard the cry and responded.

In an increasingly broken world, so many hurting souls have no one to hear them. Some have even lost their voice, too long ignored, mocked, or punished. I think of the victims of sexual abuse, who, in community, are raising their voices to speak about what they experienced, despite the deniers and gaslighters. And I hear the voices of clergy and political leaders who are courageous enough to call out the injustices and abuses of power rampant in our culture. Fearful are the voices of schoolchildren who cry for the end of gun violence in their schools. Sane adults are speaking forcefully about the tragedy of political violence, begging for people to hear the humanity in each person regardless of disagreements, but too many chose hateful rhetoric instead.

I know the chorus of healing communities, where addicts and partners hear their own stories as others share, and after feeling so alone, these lost hearts recognize that they are at home. In my own journey, telling the story – and telling the story and telling the story – has been God’s clear call, one that I heard as I sat in my car after my first meeting with a therapist in 1991. Every time I share the story, I feel God’s powerful redemption. I’m moved and humbled by the grace of hearing from people who heard their own story in some part of mine, and who realize that they are not alone.

The needs and the calls are clear; the response is the only unknown. Will you be a voice of hope for the “Jacks” of the world who need compassion and assistance? With your help, perhaps they could be guided home.

Marnie C. Ferree

Founder, Bethesda Workshops

Growing up with horses is among my best childhood experiences. Our home at the time was in the city but in an area that had two-acre lots, and ours had stables with large, fenced enclosures across the back of the property. At various times we had a goat, a pair of Easter ducks that lived for over a decade, a pet rabbit, and even a bull calf briefly in residence. The very best animals, though, were horses. The first a neighbor brought from his farm for his son and me to enjoy when I was only six years old. A second was bought by different neighbors for their daughter, my best childhood friend, and stabled on our property. In between those two wonderful beauties, a pony surprisingly appeared on my tenth birthday in one of those magical, Disney-esque moments. (Thank you, Jones family!)

Growing up with horses is among my best childhood experiences. Our home at the time was in the city but in an area that had two-acre lots, and ours had stables with large, fenced enclosures across the back of the property. At various times we had a goat, a pair of Easter ducks that lived for over a decade, a pet rabbit, and even a bull calf briefly in residence. The very best animals, though, were horses. The first a neighbor brought from his farm for his son and me to enjoy when I was only six years old. A second was bought by different neighbors for their daughter, my best childhood friend, and stabled on our property. In between those two wonderful beauties, a pony surprisingly appeared on my tenth birthday in one of those magical, Disney-esque moments. (Thank you, Jones family!) The following story about a horse named Jack was recently shared by Rosemary Farm Sanctuary, a large rescue organization located in upstate New York.

The following story about a horse named Jack was recently shared by Rosemary Farm Sanctuary, a large rescue organization located in upstate New York.